Last time we looked at The US National Security Strategy Pillar 1: Defend Critical Infrastructure. Today, we are looking at Pillar 2: Disrupt and Dismantle Threat Actors and Pillar 3: Shape Market Forces to Drive Security Resilience.

Preventing the attacks in Pillar 1 would not be necessary if the attackers were taken off the board. Now, that is an unrealistic dream, but the federal government does have the legal authority to hold criminals accountable, but only it can detect, locate, and identify them.

Pillar 2: Disrupt and Dismantle Threat Actors

Pillar 2 has five strategic objectives:

- 2.1: Integrate federal disruption activities

- 2.2: Enhance public-private operational collaboration to disrupt adversaries

- 2.3: Increase the speed and scale of intelligence sharing and victim notification

- 2.4: Prevent abuse of U.S.-based infrastructure

- 2.5: Counter cybercrime, defeat ransomware

Pillar 2 combines law enforcement and the core element from Pillar 1 related to modernizing defenses, but instead of critical infrastructure it covers all infrastructure. While Devo can be a tool for law enforcement, we would only play a minor role in meeting that strategic objective.

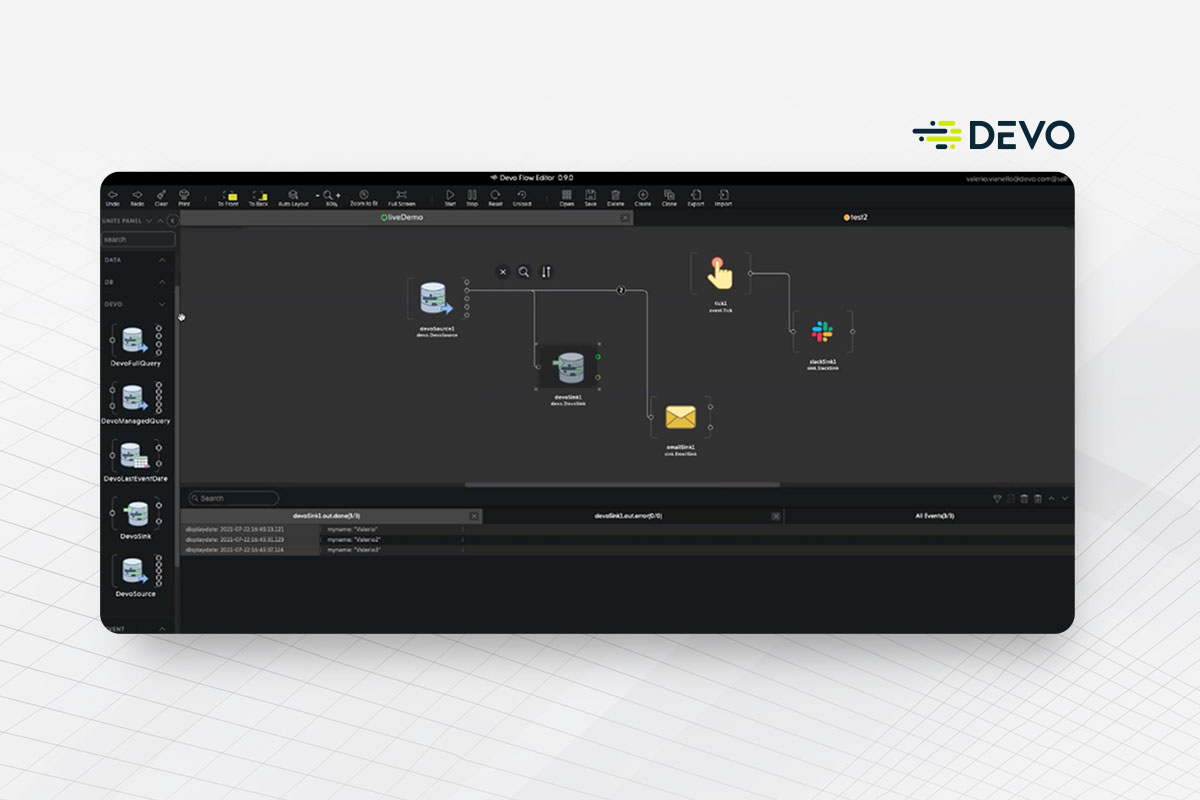

I’d like to focus here on 2.3, and specifically intelligence sharing. This is an area where the collaboration between the federal government and the private sector is critical, and where Devo has a significant role to play. As a cloud native solution, Devo can ingest threat intelligence from a wide range of sources, and to expose that intelligence to our customers almost immediately. Devo can be a conduit for this intelligence to provide it in an actionable manner to customers.

Having dug through my fair share of intelligence reports, sharing intelligence outside of the intelligence community is a tricky thing. I think the government has significantly improved their approach and maturity on this topic over the past decade or so. Sharing can help the public detect and respond to the latest significant threats, but sharing must be done in a manner that doesn’t expose sources and methods. I think passing the threat data through commercial cyber threat intelligence producers or through Devo is a sound approach to accomplish this.

To recap, Pillar 2 is about identifying, disrupting, and prosecuting cyber threat actors. This is going to be difficult given how hard attribution is to perform well, and to have it stand up in court. However, being difficult is why this pillar is so important, and why progress must be made.

Pillar 3: Shape Market Forces to Drive Security and Resilience

In many ways Pillar 3, if enacted, will be the most disruptive and drive the necessary changes in behavior across the software development industry than any of the other pillars.

The second sentence of this section states “We will shift the consequences of poor cybersecurity away from the most vulnerable, making our digital ecosystem more worthy of trust.” This transfer of liability from end-users to software producers is strategically important, and something I’ve written about in the past.

Pillar 3 has six strategic objectives including:

- 3.1: Hold the stewards of our data accountable

- 3.2: Drive the development of secure IoT devices

- 3.3: Shift liability for insecure software products and services

- 3.4: Use federal grants and other incentives to build in security

- 3.5: Leverage federal procurement to improve accountability

- 3.6: Explore a federal cyber insurance backstop

There is a lot to digest here. This pillar strives to drive two critical changes in the behavior of software developers. The first is for companies to produce secure software to start with. Secondly, is to implement some minimal set of cybersecurity capabilities in your production environments to detect and respond to cybersecurity instances. The government is approaching this with both carrots and a large stick (more like a club).

The good news is that within the strategy the federal government will establish a safe harbor, and this is where Devo comes into play. We don’t know what the exact requirements for safe harbor will be. I hope it covers both the Secure Development Lifecycle (SDLC) of software as well as production environments. My guess is that to obtain and maintain safe harbor protections, companies will need to “prove” that they meet the requirements. This means collecting the logs from the SDLC processes, as well as collecting the logs and performing detect and response within production environments.

Traditionally, Devo is used by our customers for the collection of logs from production environments and to support detect and response activities. Expanding the log collection to objectively verify that SDLC is working as designed isn’t a significant expansion of the use of Devo. There are many benefits of doing so, especially if an investigation can be traced back to a specific flaw in the SLDC processes that then can be fixed. As a software developer, I can confidently say that it is better to prevent insecure software from going into production than to respond to a breach.

The reality is that properly doing SDLC and having a well monitored production environment with a robust response capability is difficult, time consuming, and takes a lot of resources. Inside every software company there is a prioritization process and those efforts that can be directly related to the ability to sell the software will always come first. This strategy attempts to bring security into parity with traditional customer facing product features. This will lead to a slower rollout of new customer facing features which is bad for sales, but at the same time improve the security of the product which is good for everyone.

Pillar 3 of the national security cyber strategy transfers the liability from the consumer to the producer. This is a critical effort and will require honest and frank discussions between government and industry, along with compromise from both sides.